The challenge sounds like a riddle: How do you measure a whale?

Thanks to software that Ph.D. candidates KC Bierlich and Walter Torres developed, the answer can now be “One section at a time.”

“It sounds like a simple thing, but how do you measure a whale?” said Bierlich, who is pursuing a Ph.D. in Marine Science and Conservation. “You can’t jump in the water and put a measuring tape around it. You can’t grab it and pull it back in the lab; it’s huge. Before drones came along, the field was limited to measuring whales that had stranded on beaches, were intentionally killed, or were photographed from airplanes, which can be challenging, expensive, and dangerous. Drones allow for a safer, affordable, and efficient way to non-invasively take measurements of whales in real time.”

The first papers on whale research with drones came out in 2015, and in the five years since then, drone usage has quickly gained traction in the study of marine mammals.

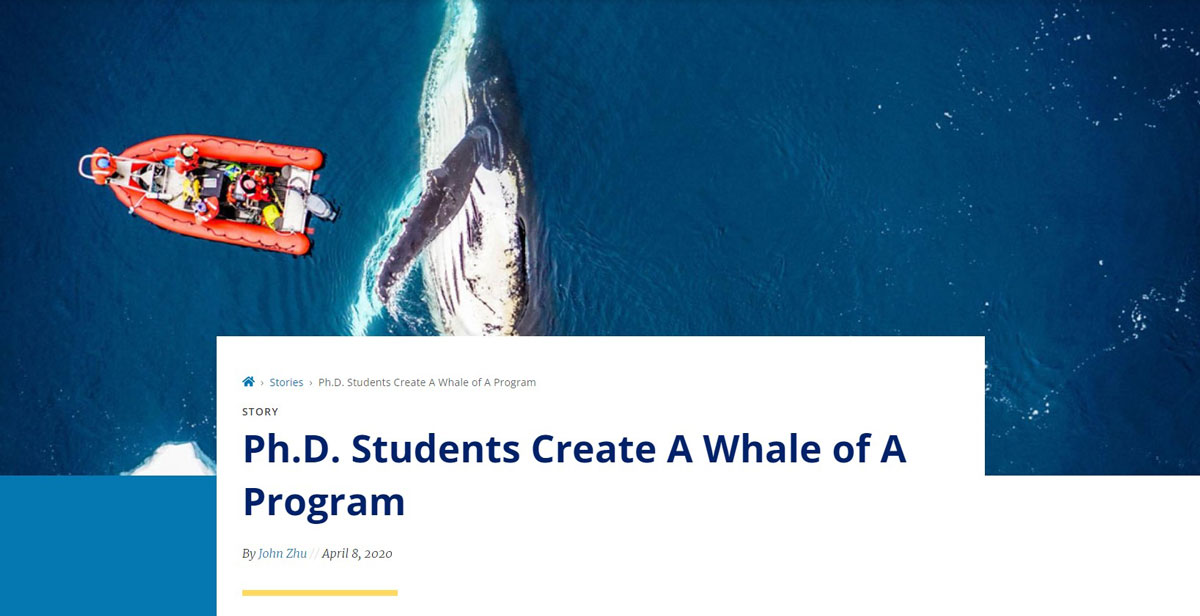

Now, all Bierlich has to do to measure a whale is maneuver a small, inflatable boat over swelling Antarctic waters, assemble his drone, launch it from his field partner’s hands, fly a moving object over a moving object while standing in a moving object, and land the drone back in his field partner’s hands without crashing it into the water, popping the inflatable boat with the drone’s propellers, or slicing off anyone’s fingers. Piece of cake.

And after all that, there is still one more obstacle—the software. Just as drones are still a new tool in the field, it is relatively early days in the development of software for analyzing the images taken with drones. Bierlich said the main software that is currently used, ImageJ, is powerful but lacks some features crucial to his research.

Bierlich is studying how much fat reserve humpback whales need to build up in their Antarctic feeding grounds to survive their annual migration to their breeding grounds around the equator, and how that might be affected by climate change. To do that, he needs to measure the width in proportion to the length of the whales in his drone images. In particular, he needs to be able to divide a whale into sections and measure the width of each section.

“I want to know how healthy a whale is, how fat it is—a fat whale is a happy whale,” he said. “By being able to take a length and divide that length into widths and see how fat it is down the body will help me assess how healthy it is. ImageJ is really good at measuring very detailed things in an image, but it can’t divide a length based on widths.”

So Bierlich started thinking about developing his own software. He wasn’t a programmer, but Torres, a good friend and fellow student in the same Ph.D. program, was. Over two years they collaborated to develop MorphoMetrix. They released the program as open-source software last summer and published a paper about it in January.

In addition to being able to measure a whale’s image section by section, the program also uses a simple point-and-click interface, making it usable without coding experience. It can also be used to measure any animal, not just whales.

The software has come in handy as Bierlich’s collection of whale images has grown. Whereas sample sizes have traditionally been very limited in his field, the use of drones has allowed him to photograph significantly more animals.

“I have over 300 animals I’m using in my analysis, which is almost unheard of for this type of work,” Bierlich said. “So this software has been great for quickly going through a lot of images. It’s very fast to be able to measure what I want, and I can measure a bunch of different things other than just the total length and width. I can measure different parts of the whale—like parts of the skull—things we really couldn’t do. Now we can measure live animals and compare populations to see if this population is more healthy, or if they may have different diets based on their skull size. There are all these new questions that we can now answer.”

Bierlich demonstrated the software at a conference of marine mammal researchers and received enthusiastic responses. He and Torres plan to update the software in the future based on feedback from other researchers.

"Because it's written in a friendly programming language—Python—and available open-source at Github, we also hope users will add their own custom functionalities to it, simultaneously meeting their own needs and making the software better long term," Torres said. "Of course I have my own list of features I think would be cool to add, but the important thing to do now is to listen to user feedback and focus on that. The software has benefited enormously from user feedback, so a huge thank you to everyone who was willing to try it out!"

Bierlich is also working with former Duke student Clara Bird, now a graduate student at Oregon State, to develop an add-on tool that automatically calculates other size-related metrics and organizes the measurements made in MorphoMetrix.

They are not the only ones working on software for analyzing drone images. Other labs have been creating their own tools as well. Bierlich said his hope is that their work on MorphoMetrix can help establish a standardized set of tools in this fledgling area of research.

“I want it to be collaborative—that’s the whole point for making the software open source, so it’s available for everybody,” he said. “It’s been really fun to talk with these other labs to collaborate together and build the best practices for everyone to follow and make it easier for people in the future.”