I’ve decided to try something new on this blog. Every so often, I’ll take a look back at a project I worked on. I do this not to show off the piece, but rather because I find it helpful to lay out my thinking process and dissect what I think went well and what could be improved with the benefit of hindsight.

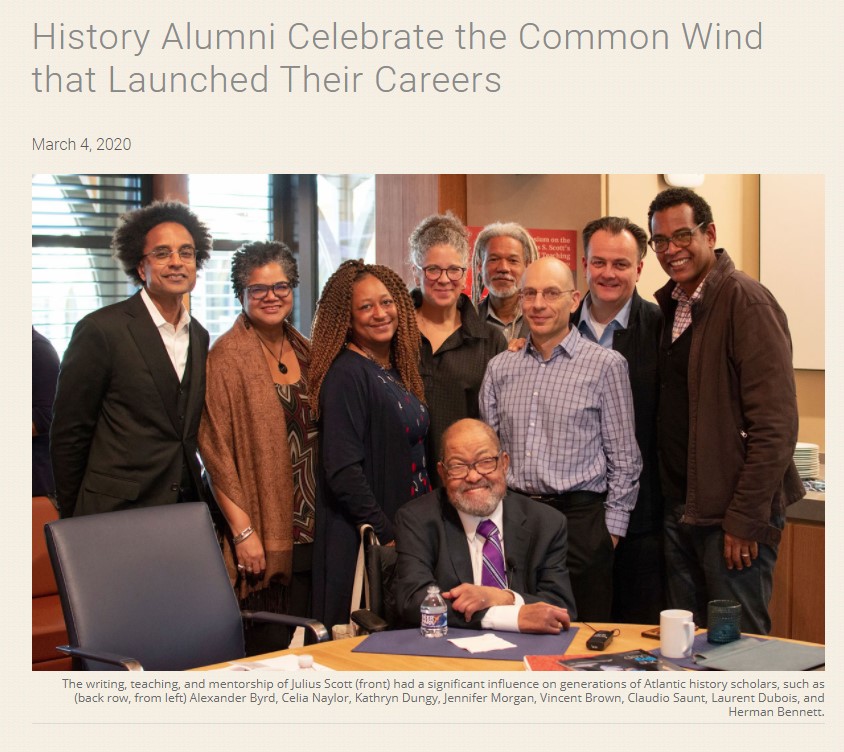

The first piece I’ll dissect is a story I wrote in March 2020 about an event hosted by my organization, the Duke Graduate School, in honor of history PhD alumnus Julius Scott, who had recently published a book based on his dissertation from 30 years ago. The daylong event was a cheerful reunion between Scott and seven other Duke history PhD graduates that he taught during his time as a faculty member at Duke, who were all now established scholars and had returned to sing their mentor’s praises. I attended about 2 hours of the event to take pictures, and wrote the story based on my mental notes and a recording of the event.

One thing I particularly liked about the piece is that it avoided the path of least resistance. When covering a multi-speaker event like this, it can be easy to fall into the “Person A said X, and then Person B said Y, and then Person C said Z …” pattern. That approach focuses on the news of an event being held: Who said what? When? Where? Certainly there are times that call for that approach, but it can also make for a rather disjointed flow, with the story jumping from one quote to the next with some awkward transition sentences thrown in between, loosely held together by the mere fact that they were all things said at the event.

Of course, some of this is driven by the event itself: Sometimes the subject matter doesn’t lend itself to a richer treatment, or the speakers don’t give you the amazing quotes that make a story come alive. Some of it, though, also stems from decisions by the writer at the outset. In this case, I decided early on I didn’t want to focus on the newsy aspects of the event itself. Rather, I wanted to build the story around several core themes:

- The idea of mentorship, a critical component to graduate student success and something that the Duke Graduate School emphasizes (I guess you can call it one of our talking points). This event clearly illustrated the fruits of good mentorship.

- The interesting story behind Scott’s book, which was three decades in the making.

- The fact that all the scholars speaking at the event were scholars of color, which illustrates the importance of intentional efforts to create diverse graduate student cohorts.

To accomplish this, I needed to move away from the event as the focus of the story and instead use the event as the springboard for diving into the deeper, more interesting aspects. In other words, the event is the mechanism or framework through which I tell a story, rather than the story itself. To make room for those other aspects, I more or less condensed the “event as news” portion of the story into the first three paragraphs, starting with the two-paragraph lead:

One after another, they took their turn at the mic—seven Duke history Ph.D. graduates, now all established scholars. One after another, they unspooled memories and introspection on how the guest of honor, Julius Scott, had shaped their lives and careers.

To Alexander Byrd, Scott was his first history professor and his first black professor. To Jennifer Morgan, he was the Ph.D. adviser who gave voluminous feedback, even long after they had both left Duke. For Claudio Saunt, he was to Atlantic history what Duke Ellington was to jazz. For Vincent Brown, he expanded the boundaries of what history could be. Kathryn Dungy reveled in the scholarly community he built around his armchair. Celia Naylor remembers her surprise and delight at seeing her home island’s history and people featured in chapter one of his seminal work. Herman Bennett has a copy of that work on every laptop he has ever owned.

This lead accomplishes several objectives:

- It condenses the “who said what” part of covering the event. It mentions every speaker and provides a memorable tidbit from each’s remarks.

- It names all the participants without resorting to a paragraph to the effect of “The participants included X, Y, and Z,” which can disrupt the narrative flow.

- It presents the remarks of seven individuals in a way that connects them with a common thread, so that they are not just a hodgepodge of quotes, but rather all pieces revolving around a specific theme (in this case, the notion of Scott as a mentor).

- The second paragraph uses the parallel structure of “To so-and-so, Scott was X” to amplify the power of each individual’s remark, so they are not just connected thematically, but also structurally. (I do wish I could have kept the last two individuals — Naylor and Bennett — to the exact same sentence structure, but content of their particular remarks just would not have quite fit that construction).

The next paragraph does the yeoman’s work in laying out the who, what, where, when, and why of the event (see highlighted parts below):

The seven scholars were speaking at a February 29 symposium at Duke. The Graduate School and the Forum for Scholars and Publics hosted the event to celebrate Scott (Ph.D.’86) and his book, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution.

Essentially, this marks the end of the portion of the story that covers the news of the event. That leaves the entire rest of the story for a more featury treatment of the themes outlined above, starting with mentorship. The next four paragraphs include a couple moments that show, rather than tell, the bond of the mentoring relationship between Scott and the seven scholars.

First, the mentor listens to the mentees describe what he meant to them, enhanced with an observational detail that could only be gathered by being there in person:

As the mentor listened and wiped away the occasional tear, the protégés recounted what his scholarship, mentorship, and teaching meant to them and to the study of Atlantic history and the African diaspora.

Two paragraphs later, the mentees’ sentiments are reciprocated with a quote from the mentor, which builds on the emotions conveyed by the tears mentioned earlier:

“You all really were the salt of my life for many years,” he said. “I’m glad to see so many of you have become so important and successful in the profession you have taken up.”

Those two passages point to each other, bookending the four paragraphs focused on mentorship. Of course, that’s not something you set out trying to do, but when the material presents the opportunity, it’s a nice little bonus.

The piece then moves on to the backstory of Scott’s book. That backstory is interesting enough for a whole story unto itself, but that story had already been published in multiple places, so instead of writing it again, this piece provides an abbreviated recap, links to one of those fuller stories, and includes a quote from one of the scholars that belongs in the “a quote so good you structure the story to fit it in” category (and so I did):

“A lot of people talked about how difficult it was to get the copy of Julius Scott’s dissertation out of the library, and that was because we were all passing it around like an underground mixtape,” said Brown (Ph.D.’02), now a professor at Harvard. “It was a historiographical deep cut that we all needed to hear.”

After a few paragraphs on the book, the story transitions into the final main theme: the fact that all the scholars were graduates from a time when the history department made a concerted effort to recruit more students of color. This was one key reason The Graduate School co-sponsored the event — to look back and celebrate the fruits of that labor. A current member of the school played a key role in those efforts, so it was important to work that tidbit in there, but I also wanted to do it in a way that felt natural, rather than as if we were tooting our own horn. So, I worked it in through these three paragraphs:

In between describing The Common Wind with words like “prescient,” “redefining,” and “transformative,” the symposium participants also recalled how Scott helped cultivate a community of like-minded scholars of Atlantic history while he taught at Duke.

The participants had come to Duke at a time when The Graduate School was making an intentional effort, led by Senior Associate Dean Jacqueline Looney, to recruit and support more black Ph.D. students, an effort that later earned an Equity Award from the American Historical Society.

“During that period, we had the perfect mix,” Looney said. “We had amazing students who were drawn to the kind of work our faculty members were doing, a department that was committed to recruiting more black students, and mentors and teachers like Julius who challenged them to push the intellectual boundaries of their field.”

The second paragraph communicates the role that The Graduate School played and the fact that the effort was recognized with an award. The third paragraph, though, points the attention right back to the students, the faculty, the department, and of course, the guest of honor at the event.

(I perhaps could/should have written a bit more about that institutional effort to recruit scholars of color. I was trying to strike a balance between going more in-depth on a sub-topic and not venturing too far from the main storyline (Scott and his mentees). In the end, I decided to hew closer to the latter, but I can see arguments for a bit more ink on the former.)

Taken together, these three paragraphs provide a transition from talking about Scott to talking about the institutional effort to recruit more scholars of color and then back to Scott again. This does two things: 1) Connect the individual — Scott — to the bigger picture of recruiting and training more diverse cohorts; and 2) leaves us at the end of that passage in a position to close the story with the focus back on the guest of honor, thus tying it back to the beginning of the story. The story ends with a quote:

“He never pushed me out when somebody else would come into the room,” Dungy said. “It became a community of scholars, and we were all working on this project of redefining history. … And we have changed the world. The scholarship that is out there—the paradigm has shifted, and it’s because of The Common Wind, and we’re that wind.”

Every writer has certain habits and tendencies that border on overuse, and one of mine is the preference for ending the story on a quote. In this case, though, I think the closing quote justifies this treatment, given that it touches on all three of the main themes, and, as a bonus, ties into the title of Scott’s book. In a sense, it brings the narrative journey back to where it began: The spotlight is squarely on Scott and his work, and behind him, stands the unmistakable broader influence his work had on the field, embodied by his mentees.

Miscellaneous

- In addition to writing the story, I also photographed the event and shot some B-roll, which went into the event video that a colleague from the co-sponsoring organization produced. That made for a nice multimedia package. I always enjoy projects where I have a hand in both the visual and text side of things.

- I went back and forth on a couple word choices in this sentence in the first paragraph:

“One after another, they unspooled memories and introspection on how the guest of honor, Julius Scott, had shaped their lives and careers.”

unspooled vs. unreeled

introspection vs. retrospective

- Aside from getting a nice story, it was just a pleasure to hear so many outstanding scholars discussing what Scott meant to them. It really drove home the importance of mentorship and the lifelong influence a good mentor can have.