The Lenfest Institute for Journalism has been experimenting with innovative local news products, and recently, it asked the following question:

If we knew where you lived and worked, how might we serve you better with local news and information?

That’s a great question, and the Lenfest piece above offered some ideas it has been playing with, such as linking stories to locations and serving up stories for people about places near them.

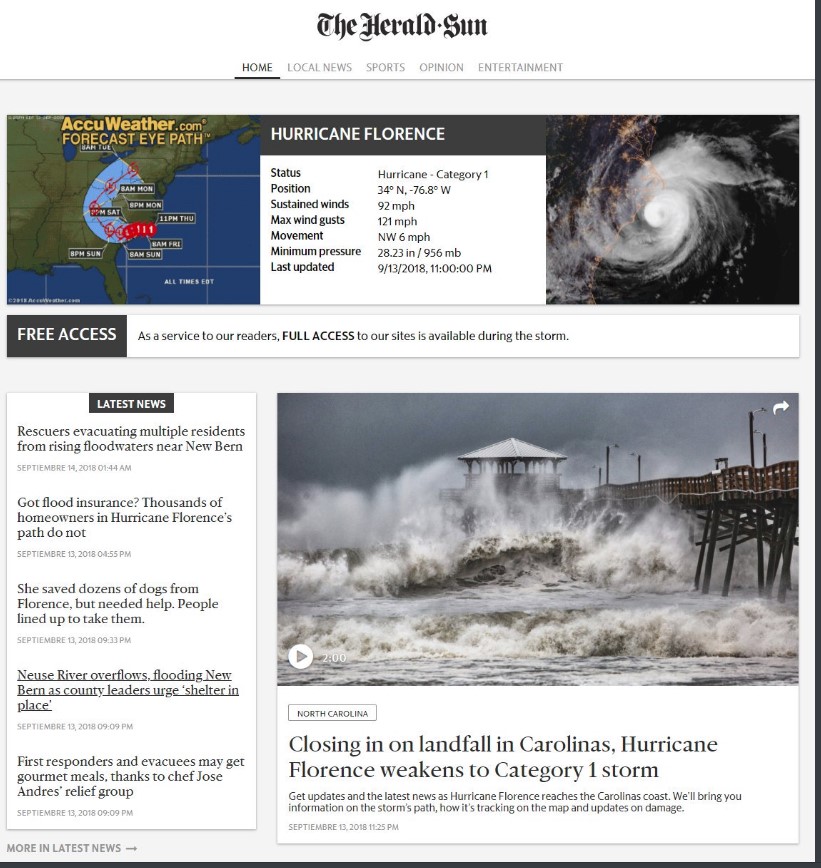

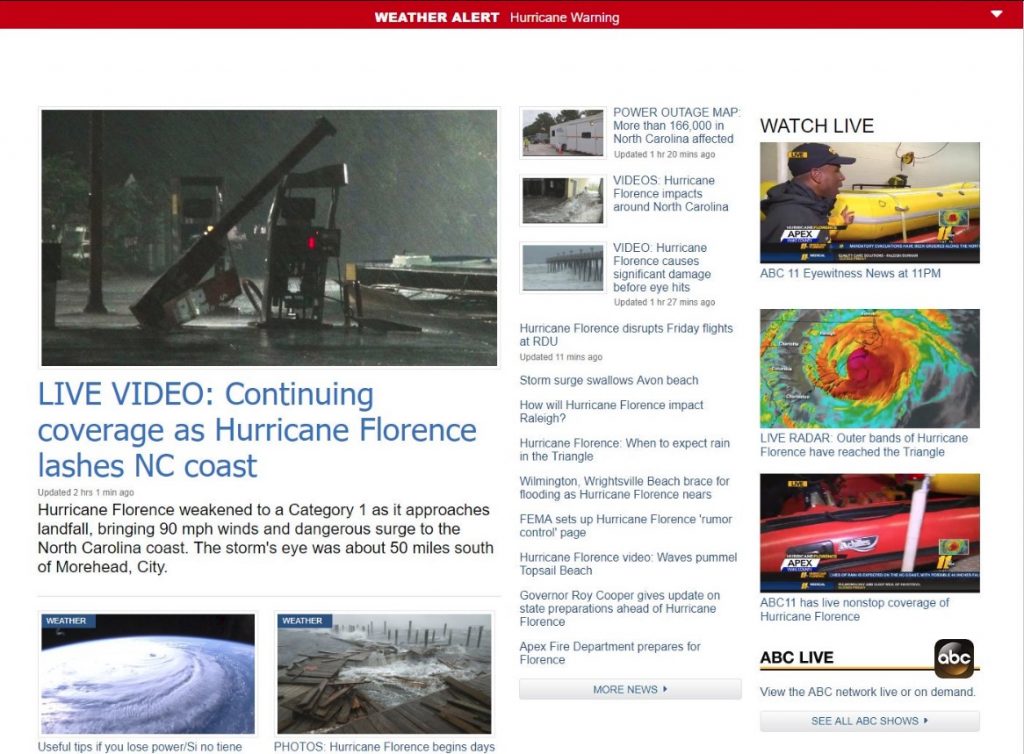

Here’s one idea I proposed last year during hurricane season. I live in central North Carolina, about three hours from the coast. For days leading up to Hurricane Florence, my news feeds were filled with reports about how hard the oncoming hurricane might hit us. Or not hit us, depending on which path it took and where in our local area one lived. On the night the hurricane made landfall in North Carolina, here’s what was on the home pages of some of the major local news outlets in my area:

All the coverage was focusing on what was happening on the coast. Make no mistake, that is important. But if you are a news outlet whose main coverage area is three hours from the coast, then you need to ask whether sending teams of reporters and visual journalists to the beach is the best way to serve your core community.

As a member of that community, here’s what I wanted to know most during that time:

- How much of a threat is the hurricane to the spot I’m standing on?

- Where can I get emergency supplies? Which store still has bread, water, milk, etc.? Which gas stations have long lines? Which gas stations still has a drop of gas left in the pumps?

- What roads are closed in the area?

- Which neighborhoods have lost power?

You know where I found that information? Facebook (yes, the Facebook that’s “stealing” all the ad revenue from news). Specifically, local Facebook groups with robust and helpful discussions where area residents crowdsourced such information. So, guess where I spent the most time looking for updates during the hurricane.

Now, imagine what a local news outlet can do in this space, with my location data. For instance, what if you could offer me a widget, either on your website or in an app, that gives me:

- the weather conditions in my area, as specific as it can be

- location-based information from nearby grocery stores and gas stations about who has what supplies left

- location-based information from the local authorities about road closures, power outages, and expected time till remedy

Properly organized and vetted by professional journalists, this can be unique, reliable, local information that I would not be able to get anywhere else — the kind of information valuable enough for me to actually hit the “Allow” button when your news website asks me for permission to send me notifications. Or, in this case, the kind of information that would convince me to let you have my location data, and maybe even more. It’s also the kind of service that builds deeper connections with your community and tangibly demonstrates the value of your work to the members of that community.

Of course, this is not the kind of thing you can pull together on the fly the day before a disaster. It requires ample planning, development (e.g., finding reliable information sources that can be tapped, compiled, remixed, and disseminated), and relationship building (such as arrangements with local merchants to report their status in the case of natural disasters).

If this sounds like a lot of information to process in a short period of time, it is. Yet local news outlets already engage in some efforts similar to this. For instance, during snow days local media outlets would compile lists of school closings. Or looking farther afield, newspapers compile results and box scores from local high school sports teams every night. That information comes from a number of sources: call-ins from the teams themselves, reports from journalists who covered a game, information shared by other news outlets, and even news wires at certain times of the year. All of those require planning, relationship building, and the development of tools and resources well beforehand.

And yes, it would likely require a lot of staff time to track and compile this information in real time during the natural disaster. And no, it doesn’t result in front-page stories about random people your reporters come across on the beach 150 miles away, and it will not get you dramatic footage of raging winds and powerful waves detonating against the shoreline. What it does do, though, is serve your readers immeasurably better than any of those things. It’s a different approach, a different mentality — one not focused first and foremost on “telling stories,” but rather on providing information that people need.

So now, who wants to make that happen?